Measuring the Unmeasurable: When Big Data Meets Populism

Populism is a political issue that is likely to represent a source of political instability (Torres, 2006). Consumers might perceive the political uncertainties and think that it is rational to save more and invest less, contributing to pessimistic economic evaluations. This is likely to create contractions in the internal demand of a country. At this point, a careful reader might raise its eyebrows and roll its eyes, reasonably thinking something like “What a nice, neat and almost lovely argument, but… don’t we need to measure stuff before analysing its impact on something else?”. That’s correct, in fact if our intent is to investigate the possible impact of populism on economic or financial parameters, then a condicio sine qua non of this analysis is to measure populism. In fact, a time-varying indicator for public attention to populist politics does not exist.

Before going any further, we need to briefly define what the term “populism” means, given the inconsistent and undefined meanings often assigned to the term (Taggard, 2000). Populism originates from the Latin word “populus”, which means “people”. Jagers and Walgrave (2007) demonstrated that populist parties constantly associate themselves with “the people”, without any specific political orientation. One of the most important drivers of the core values of populists is the so called vox populi (i.e. the voice of the people) and direct implications are their type of language, attitude and political structure. The volonté générale (i.e. general will) of the people should represent the main driver of political expression (Muddle, 2015).

To summarise, Albertazzi and McDonnel’s (2008:2) definition is considered to be the most appropriate for a concise notion of populism:

“An ideology which pits a virtuous and homogeneous people against a set of elites and dangerous ‘others’ who are together depicted as depriving (or attempting to deprive) the sovereign people of their rights, values, prosperity, identity and voice”

Over the last two decades, Western countries’ populist politics have overwhelmingly emerged amongst mass media’s sights. People who are interested in these topics are likely to search specific keywords on the internet concerning ongoing populist politics or events (e.g. Brexit). Here is where big data comes into play and it might help to measure populism, but how?

Google Trends can display public interest in issues related to populism. The Google Search indicator is a tool realised by Google Inc. that provides the search volumes’ figures of the keywords typed in Google’s search bar. It scales the number from 0 to 100, with 100 being the highest level of search volume and 0 the lowest in a given period. Below, the definition available on the Google Insight website:

“Google Trends analyzes a percentage of Google web searches to figure out how many searches were done over a certain period of time.

For example, if you search for tea in Scotland in March of 2007, Trends analyzes a percentage of all searches for tea within the same time and location parameters.”

People in the US may search populist-related keywords such as “border control”, “Donald Trump” or “Tea Party”. For what concerns the first two keywords, well, they are quite widely mentioned in today’s society as populist issues (The Economist, 14th July 2016; Woodward and Costa, 2016; The Editorial Board, 2016). Probably someone have forgotten the Tea Party, a populist movement born in 2009 following the financial crisis of 2008. The movement mainly focused on arguments such as the bailouts of failing banks, insurance and automobile companies, and was considered a populist party (Minkenberg, 2011; Ray, 2016; Ballhaus, 2014).

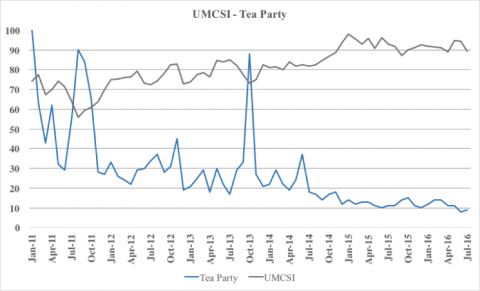

The search volume of this last search term is taken as an example and compared with an economic leading indicator: the UMCSI (pictured in Figure 1). In the US, the Survey Research Center at the University of Michigan conducts a monthly survey which reflects consumer’s perception in several areas. The objective of the UMCSI is to summarise short-term economic evaluations considering the following arguments: consumers’ economic expectations about the future (forward-looking), consumers’ economic insights about the future considering the past (backwards-looking), personal financial situation and country-related business climate.

In a nutshell, the UMCSI is an index designed to capture the US consumers’ insights regarding their activities of saving and spending and the economic condition of the United States.

Graph 1: UMCSI and the search volume for Tea Party. The blue line represents the frequency of searches for “Tea Party” and the grey line is the UMCSI data. Observations are taken between January 2011 and July 2016.

The observations considered in the graph are deliberately downloaded from January 2011 to July 2016 for both variables. It can clearly be seen that the movement has lost most of its audience after July 2014, as people’s attention moved to other ongoing issues. However, during that period (i.e. approximately between January 2011 and October 2014), a negative correlation between the two variables can be noticed several times. The highest Tea Party peaks (July 2011 and October 2013) correspond with two strong UMCSI troughs. Moreover, the same relationship is observed in April 2011 and October 2013.

According to the graph, the more people search for the populist movement, Tea Party, the gloomier are consumers’ economic evaluations. Obviously, this tiny example does not allow the reader to stand up and shout “Eureka!”, but it is a novel idea that may be implemented in further analyses to measure an abstract concept like populism. This type of analysis is intended to capture how interested people are in populist politics and could be improved following various paths. For example, the Google search volumes might be compared with other economic variables or some keywords might be better tailored than others to reflect public attention to populism. One may think of dozens of other limitations of this little study, but those would, in the process, lose the primary message. Once again, the point here is to introduce a simple idea, which takes advantage of the great potential of the digital environment of people’s everyday life: big data.

References

Albertazzi, D. & McDonnel, D. (2008). Twenty-First Century Populism. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Ballhaus, R. (2014). A Short History of the Tea Party Movement. [Online] Available at: http://blogs.wsj.com/washwire/2014/02/27/a-short-history-of-the-tea-party-movement/

Jagers, J. & Walgrave, S. (2007). Populism as political communication style: an empirical study of political parties’ discourse in Belgium. European Journal of Political Research, Vol. 46, Issue 3, 319–345.

Minkenberg, M. (2011). ‘The Tea Party and American Populism Today: Between Protest, Patriotism and Paranoia’. der moderne staat – Zeitschrift für Public Policy, Recht und Management 4, no. 2.

Muddle, C. (2015). “The problem with populism”. [Online] The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/feb/17/problem-populism-syriza-podemos-dark-side-europe

Ray, M. (2016). Tea Party movement. [Online] Encyclopædia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tea-Party-movement

Taggart, P. (2000). Populist. Open University Press.

The Economist (2016). Past and Future Trumps. [Online] The Economist Newspaper Ltd, London (14th July 2016). Available at: http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21702193-insurgent-candidates-who-win-nomination-tend-transform-their-party-even-if-they never?fsrc=scn/fb/te/pe/ed/pastand futuretrumps

The Editorial Board (2016). The Border Patrol’s Bizarre Choice. [Online] The New York Times. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/05/opinion/the-border-patrols-bizarre-choice.html?_r=1

Torres, V. (2006). The Impact of ‘Populism’ on Social, Political, and Economic Development in the Hemisphere. Ottawa, Ont.: FOCAL.

Woodward, B., Costa, R. (2016). Trump reveals how he would force Mexico to pay for border wall. [Online] The Washington Post. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/05/opinion/the-border-patrols-bizarre-choice.html?_r=0

Related posts:

About Giacomo Teodori

Related posts

-

Elezioni francesi: la corsa per l’Eliseo di ...

26 Aprile 2017

-

Brexit: un’intervista in diretta dalla Germania

15 Novembre 2016

-

Populismo in Italia e nel mondo: ci ...

21 Settembre 2016

-

Come fallì l’economia populista di Allende

11 Settembre 2016

-

Grillo è il Fabio Volo della politica

13 Ottobre 2012

About Giacomo Teodori